An Interview with Artist in Residence Will Jacks

Sarah Posey: Where are you from?

Will Jacks: I live in Troy, Alabama now. I'm originally from Cleveland, Mississippi, which is in the Mississippi Delta. So about 100 miles from Memphis.

SP: Has it impacted your work?

WJ: Absolutely. I think all of our artistic work is impacted by all of our experiences in life. So my experiences in the Mississippi Delta in particular are always in my work, whether I try to put it in there or not.

SP: What is your artistic backstory?

WJ: Oh gosh how long do we have? I was always drawn to the idea of a creative lifestyle.

As I was growing up, I did all of the typical things. I hunted and fished and played football and baseball and all of those activities as a young boy in the Mississippi Delta. But the people I seem to admire most were always artists. And I think now, after years of consideration, it was a sense of freedom that I saw in these individuals. I knew very early on that I wanted to live a life of creativity, but I didn't quite know what that meant. And I had a wonderful art teacher, Pat Brown, when I was a sophomore in high school and again when I was a junior, and without her I don't know that I'd be where I am today.

But I eventually went to college, played baseball, football, and then towards the end of that tenure, navigated my way back to creativity and I explored writing. That didn't quite work the way that I'd anticipated. And I discovered photography when I was in journalism grad school in the early to mid nineties at the University of Mississippi and just kind of continued to follow that interest. I’ve almost always been intrigued by learning new things, learning new ways to make, learning new skills with the equipment, learning new ways to translate ideas. And I just kind of kept chasing that. And here I am today.

SP: What is the process for this body of work that you've been working on?

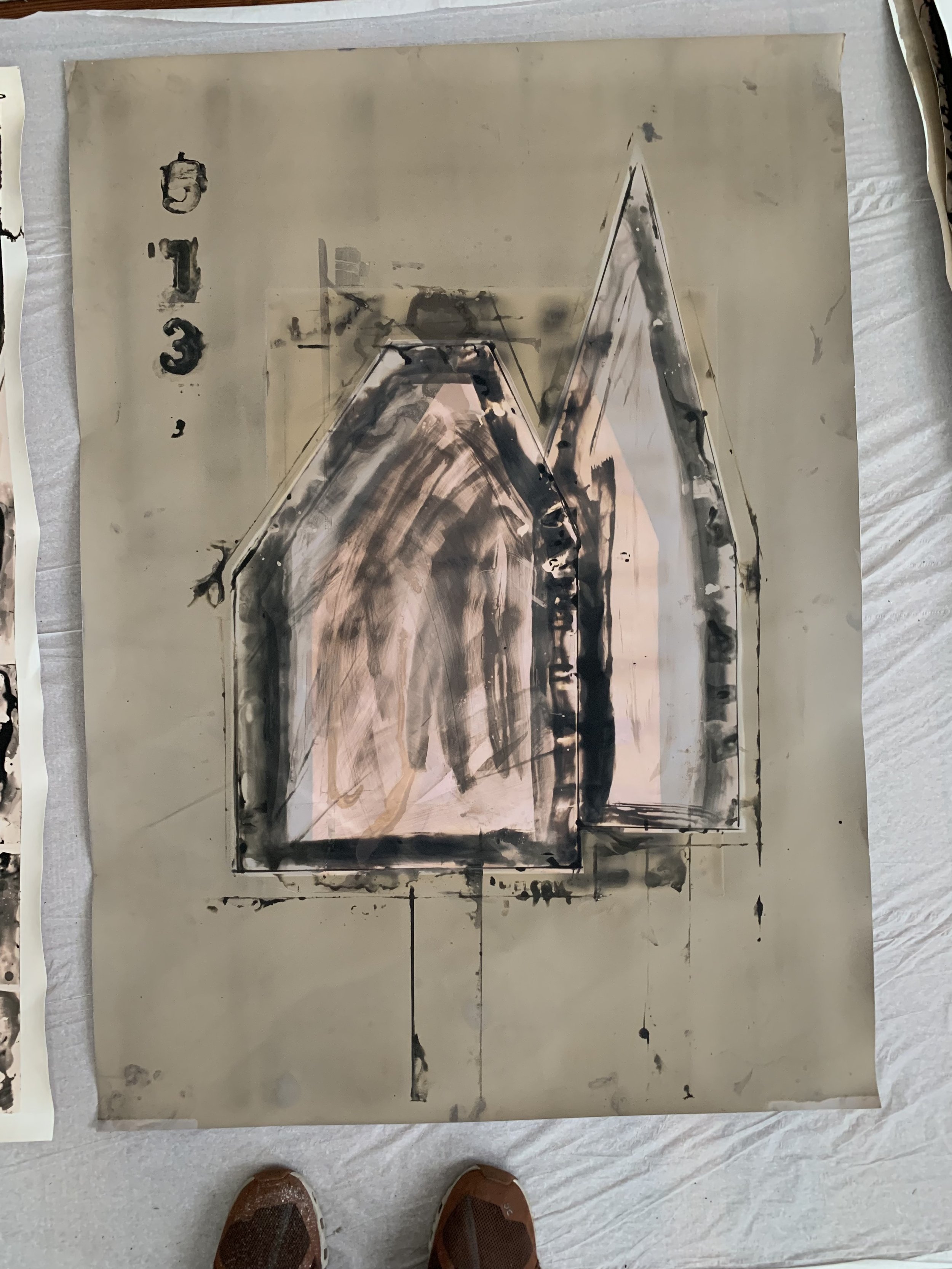

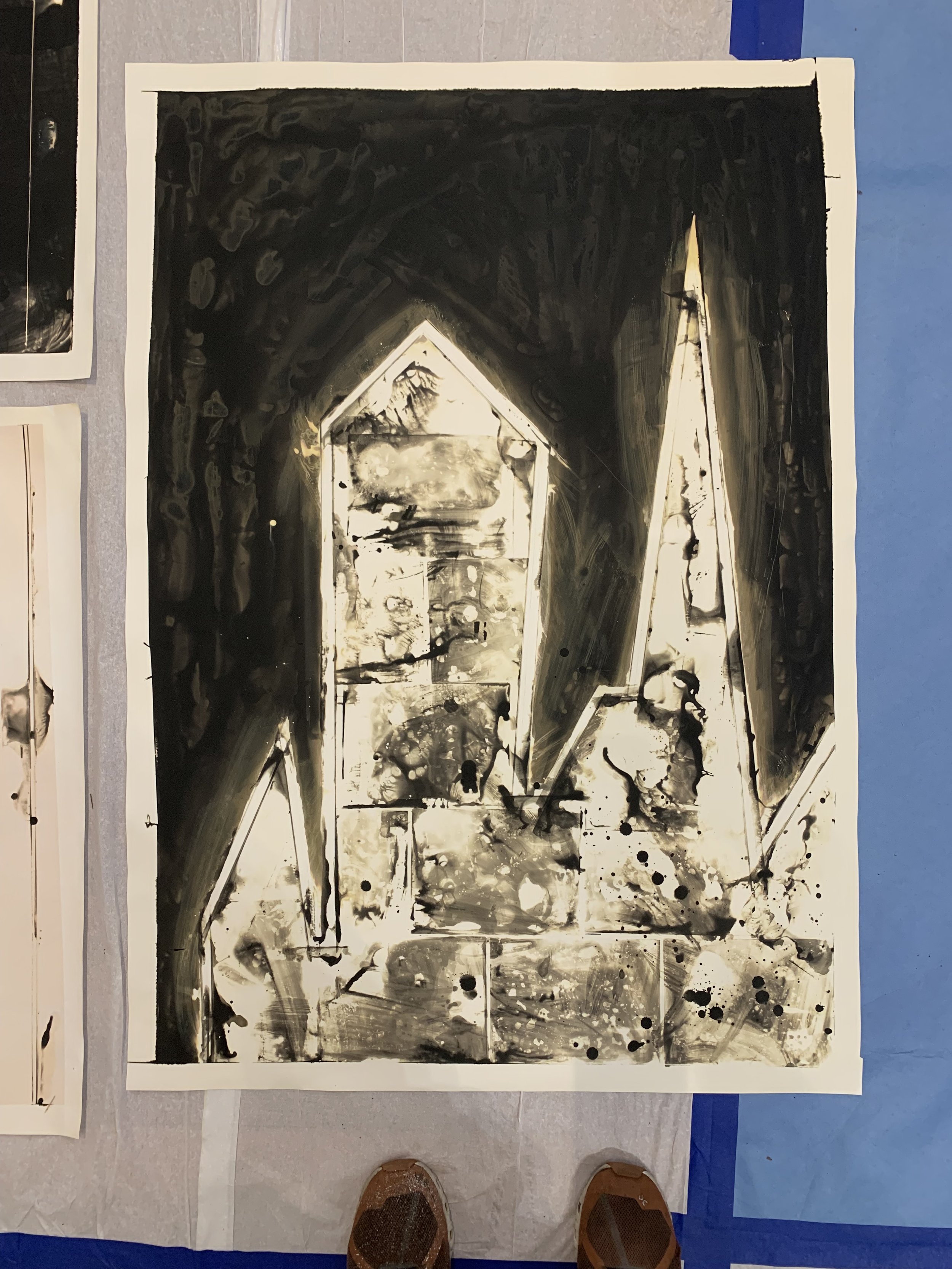

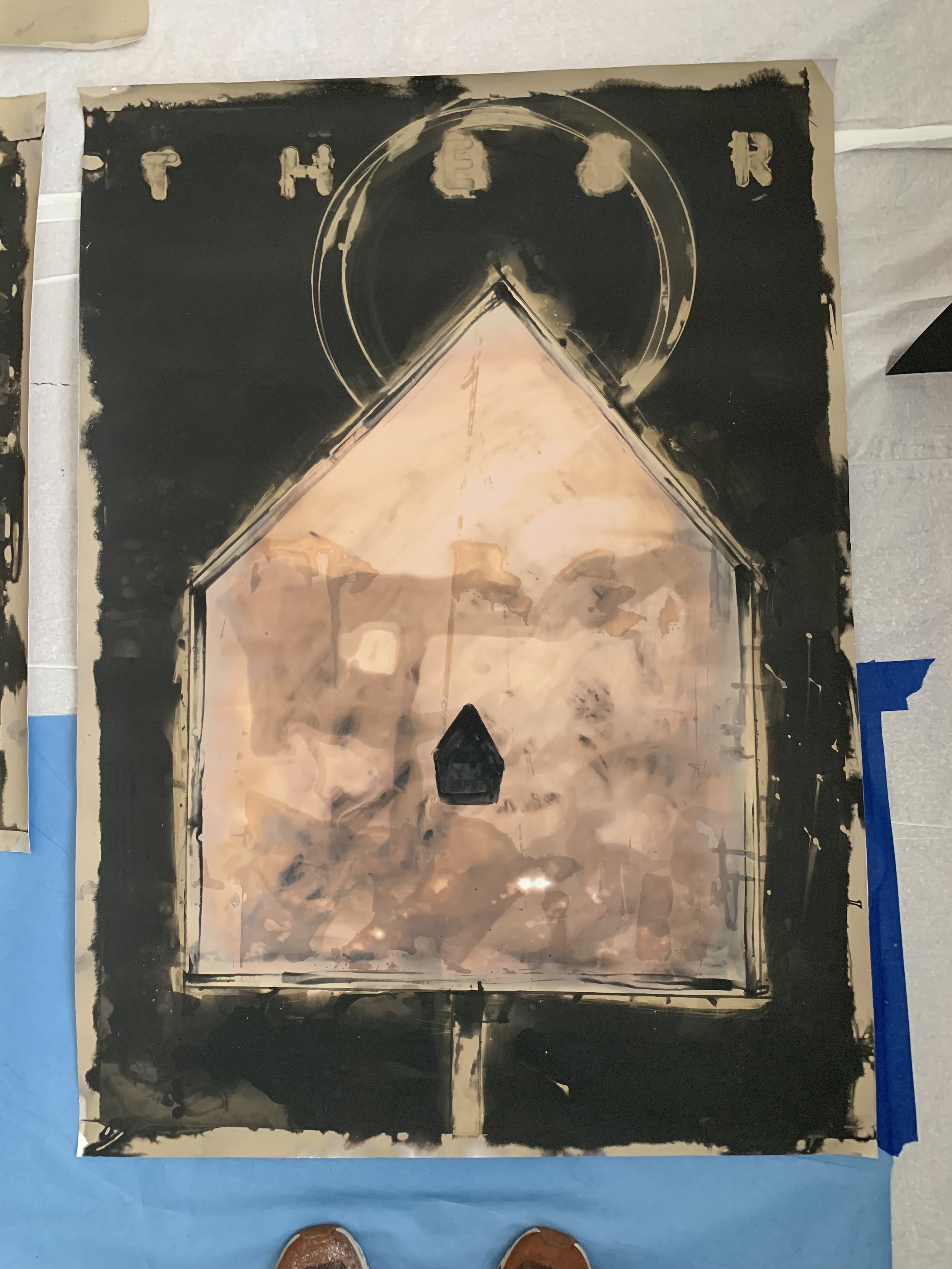

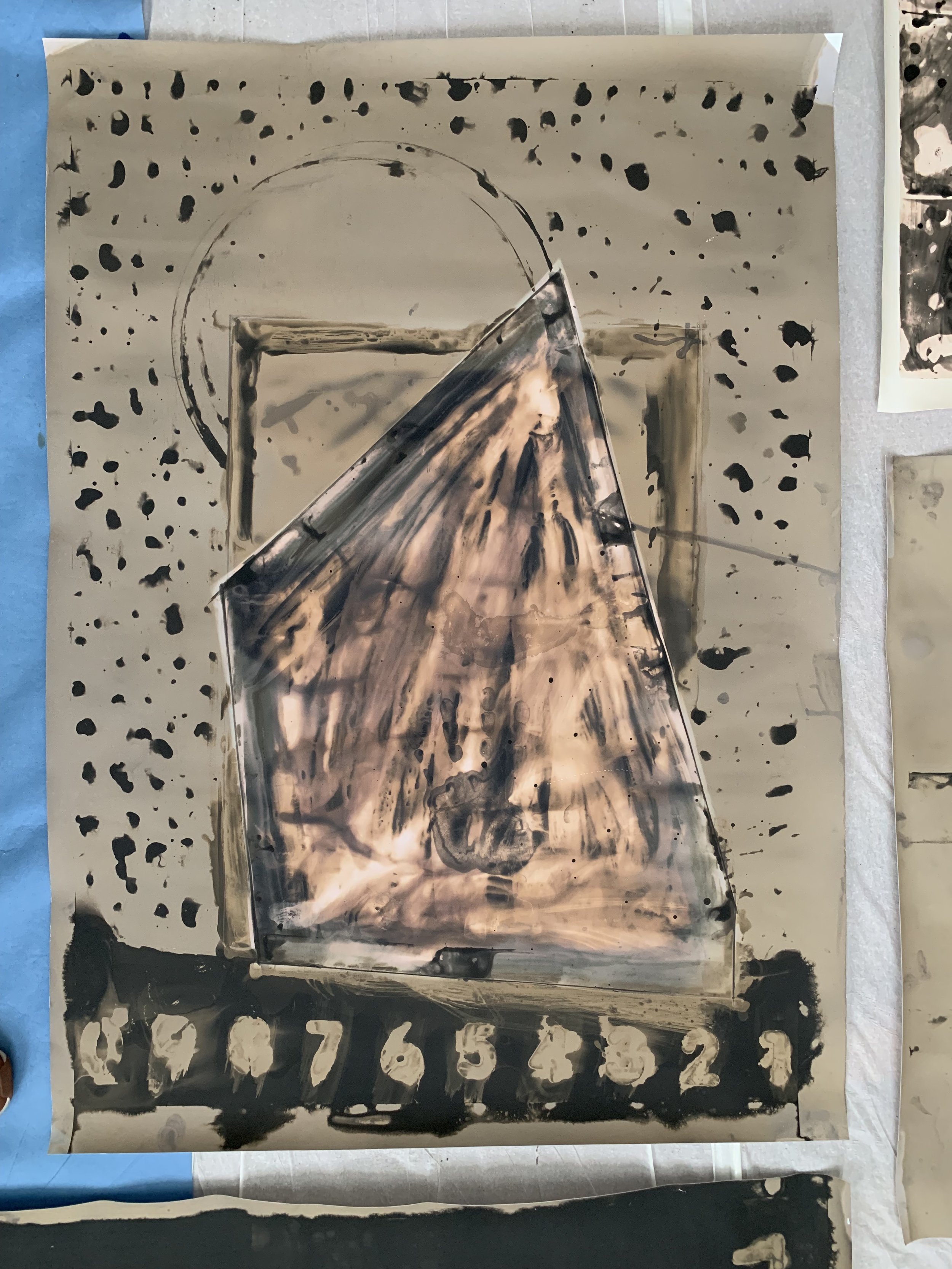

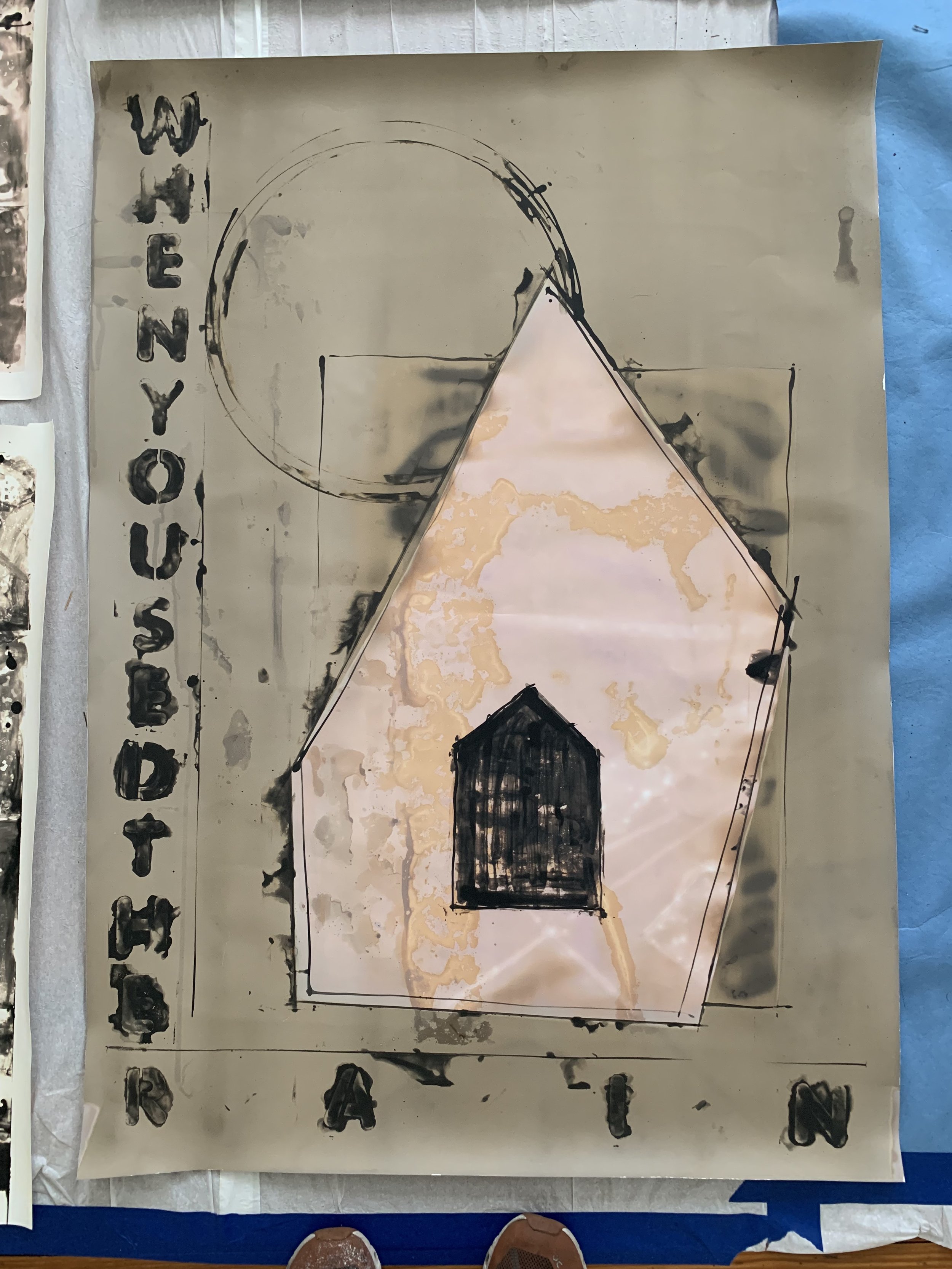

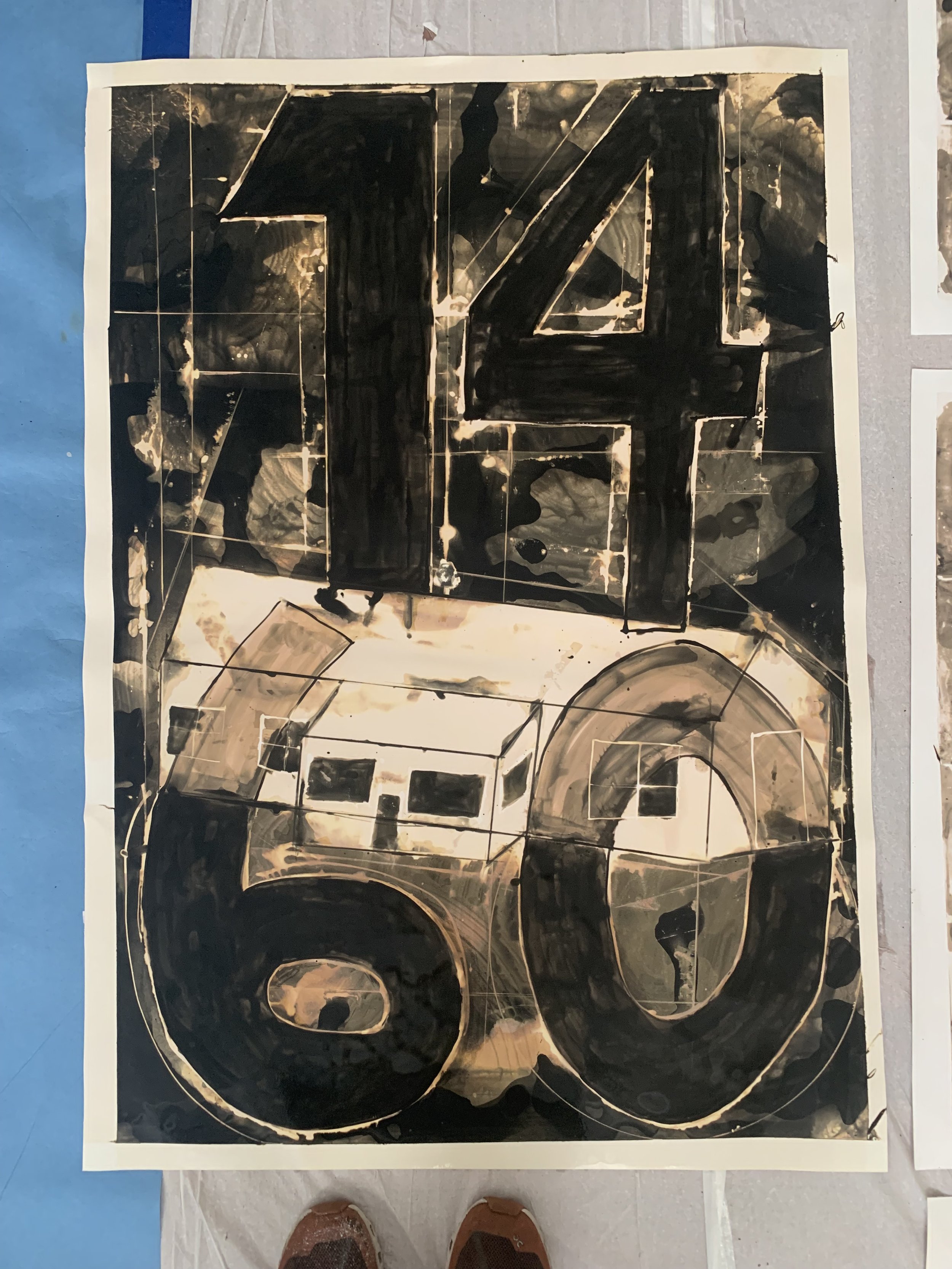

WJ: For the body of work that I'm making now, I'm using very traditional darkroom material. So I'm using a fiber based silver gelatin paper. So that's a paper that's light sensitive, the same type of paper that Ansel Adams would have taken into the darkroom, for example, to make his prints.

I'm using the same chemicals, developer and fixer and water to manipulate the paper's surface, but I'm using these materials in non-traditional ways. So I'm not using a darkroom, I'm making all of these prints in the daylight. I’m using things like tongue depressors and paint brushes and pencils and plexiglass plates and poster boards to leave imprints on the paper or make imprints on the paper. And so it's very similar to drawing, to painting. Mark making is extremely important. Yes. And so these are photographs, but they're made without the use of a camera. And they're made primarily from memory, rather than reference. Direct reference.

SP: And why did you choose this process?

WJ: For about six years now, I've been really interested in photography as an object for that concept of mark making. As I have explored more of the history of photography and come to understand that more and also understand myself more through that, I've recognized that I've always had a little bit of a, what's the word I'm looking for? I've always felt a little uncomfortable with photography as a means of expression, primarily because of its direct relationship with reference, its direct relationship to a person or a place or a thing. So the way that we normally have grown accustomed to photography is by showing something else.

But I also knew through my own making that it was always a series of choices. I would decide what to put in the frame. I would decide how to frame it. I would decide whether to show that image to the world or not. So there was a level of mark making by photographers that I think over time we as society have grown less and less and less aware of. And the idea of “photo or it didn't happen,” this complexity of photography with the truth and, and what felt like to me too often a dismissal of the photographer's role in the making became something that I was increasingly curious about. And so I wondered, what exactly defines a photograph?

When does something stop being a photograph? Is it just about the materials that you use? Is it about the way it looks? Is it about what the image itself references? I was very interested in a photograph as a unique object. And so I began exploring all of these things in my making, moving away from more of a documentary style of photography and to the point where now I rarely use a camera at all in my photos.

SP: So I take it you're a process based artist?

WJ: Very much so.

SP: So what about that appeals to you?

WJ: The meditation of it. You know, early in my career, I think I was very interested in the results. Where did the work wind up? Were other people interested in the work? And inevitably I was generally unhappy with the work that I was making.

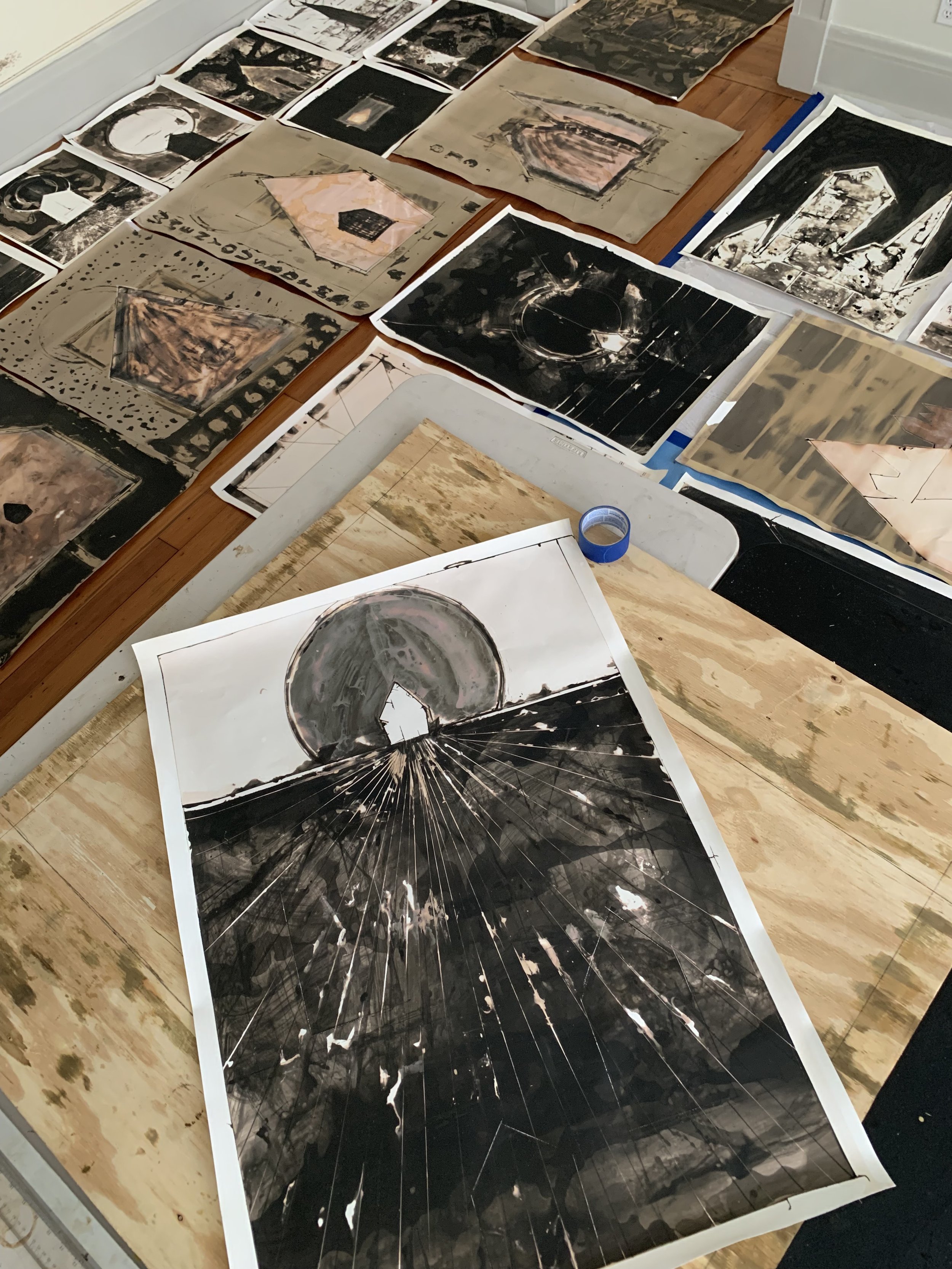

As I've matured as a human, lived through life experiences, but also as a maker I've learned that while I certainly enjoy accolades and I want people to respond in positive ways to my work, I'm less driven by that. And I've found that it's a meditative process for me to make. And so I'm generally my happiest, I'm most at peace when I'm making something. And for this particular body of work, the way that it's made requires me to be present with the work. I can't leave the print and come back tomorrow and complete it, for example, the way I might be able to with a painting or even a drawing. I have to start it and I have to finish it all in one sitting.

And that creates for me a very hyper presence. And once I make a mark on the paper, I can't take it back. I have to be deciding as I'm making it. I have to have some idea of what I wanna make, but then also be making decisions at that moment. And so I'm very present in that making and I find that that process for me is a really healthy one.

I mean, even now, I'm making this work and I don't know if it's any good or not from the sense of whether or not other people will respond to it. I know that it's good because I've really enjoyed making it. And I've learned new things. I have refined my craft. There are things that have popped up previously in my head of, “I wonder if I could do this or wonder how I can do that.”

And particularly over the course of the summer and being here at the Mary C. and being able to come in every day, more or less, and focus just on making work that I've gotten better and better and better at those things. So in that regard, it's been extremely successful to me, whether or not other people will “get it” or “like it.”

Over time, I have grown to trust that more and what I've learned is that generally if I put myself in a place where I am really Excited by the way that I'm making, whatever that process might be for that body of work, that's the first thing I get excited by.

SP: And do you change your process for each body of work?

WJ: Sometimes, yeah. Or sometimes I'll have several processes going on at the same time. But if I do that and I'm excited by it, I generally am going to follow a healthy curiosity and a healthy effort. And then from that, I seem to get more positive responses. And this body of work, I think in particular, it's relatively fast.

Some of the prints I might make in an hour. Most of them probably take me about three or four hours. But in the grand scheme of making, like, that's, that's a pretty quick amount of time to make a print. And so there also is an innate, for lack of a better term, sloppiness that happens, like I can't control the way the chemicals might bleed into certain areas of the paper, or I'm choosing not to.

And that, in turn, creates kind of an urgency in the work. And and so there's an element that I equate back to, like, my experience of listening to blues music growing up in the Mississippi Delta. And how you don't necessarily have to be the finest technician in what you make.

As a matter of fact, sometimes too fine of a technique can diminish a work. There's a human element to a rawness or little mistakes that I think are important in a body of work or that I'm drawn to in work. And so I think that comes out in the way that these prints are being made.

SP: Awesome. Yeah, I was actually going to ask you what your experience at the Mary C. has been like for you.

WJ: It's been Amazing. I mean, I went back to graduate school late in life. So I did journalism graduate school when I was in my twenties in the early nineties at the University of Mississippi. And that's where I discovered photography and I pursued a photojournalistic documentary route with my work for years. And I slowly began teaching around 2013 or so and began teaching a little bit in the journalism program at Ole Miss and a little bit in the art department at Delta State University. And I realized then that I really enjoyed the art side of things more. And once I decided that I wanted to go all in on higher ed and I wanted that to be the next transition in my career.

I spent 20 odd years as a freelancer before I started doing this. I went back to get my MFA and so that program, I was 46, seven, eight years old at that point. And in the midst of my graduate school experience, my father died unexpectedly from Bypass surgery and three weeks after his funeral my marriage fell apart. I'd been married almost 20 years.

It was tough, but I was very lucky to be Immersed in an art program at that point and I could channel all of these complicated and difficult emotions and feelings into my work, and I actually stopped caring. I was so frustrated and angry and sad and hurt and all of those things that I stopped caring anymore if my work was any good. And I just started making, and I couldn't, I couldn't make fast enough. I just had to get it out. And I was also surrounded in a formal program where the work was then being considered. and critiqued, and reviewed, and that was very healthy for me. So I say all that to say I spent two summers in Maine as part of that program. So the program that I attended through the Maine College of Art, I was able to work from my home in the Mississippi Delta during the fall and the spring, mostly. And in the summers, for two summers, I went and spent them in Portland, Maine.

So I was there for eight to ten weeks. And it was all about making, making, making, making, and then we would critique and review and things like that. And then I finished and I started teaching. And while my teaching schedule allows me a lot more free time than when I was working in an administrative position in higher ed, for example it's still really difficult to find time to sit down and actually make. And I learned a lot about my process in order to make a new body of work and find something interesting. For me, I need at least a week of exploration of not really worrying about what I'm making. I kind of start with a process usually and begin to explore that until I land on an idea that excites me.

And I learned that in grad school. And then I need several weeks to just go make, make, make, make, and I start to iron out a process of making that I can then carry forward with me and be a little more efficient with it when I go back to my teaching job. And so this summer was the first summer since I finished grad school in 2019 that I've been able to get back to that daily routine of usually in the morning I would tend to some things related to my teaching job at Troy University and then I would come in and I would have the whole afternoon to do explore this new way of making until the work began to get more and more and more refined to the point that now I've got a body of work that I'm mostly happy with. There's a few pieces that I think are really strong and there's a few that I think maybe that won't see the light of day again.

But more importantly, I'm excited by the conceptual approach that I'm making. And now when I have three, four or five hours at work once the semester starts in a couple weeks, I can go back into the studio and I can begin to make more and more of these prints. I don't have to work out the process as much. So, working here, having the space has been beautiful. Everyone here has been supportive and open and welcoming and it's been, I couldn't have asked for a better summer.

SP: What do patterns mean to you?

WJ: Oh, patterns. You've been looking at my website. Another thing that I've learned over the years is that I'm really drawn to the visual of a pattern of repetition. I think back to when I was in elementary school or middle school and how often I'd wind up doodling. I don't know if this still happens like when we used to have book covers that we would have to put over our textbooks. I don't know if that's still a thing or not, but we would inevitably mark those covers or our notebooks would always be covered in doodles.

And I've got, fortunately, a couple of folios of old notebooks and work that I made when I was 14, 15, 16 years old. And then, going back and looking at that and most of the work that after 40 some odd years, 30 some odd years, almost 40, I've not seen it and reconsider it. The work that I found most interesting was usually when I wasn't trying to make artwork and I was just doodling. And it usually was patterns repeated over and over again. Sometimes it would be a checkerboard pattern, and other times it would just be lines that get repeated. And, and so what that tells me is that when I'm happiest in my making, when I make just for the sake of making, I fall on pattern.

And that's where you begin to examine things like your own history and where you've grown up. And of course, growing up in the Mississippi Delta, I am very much conditioned by that agricultural lifestyle, that pattern of every year, like each month. You know what's going to happen at this point in the year in the Mississippi Delta because of the pattern of it happening over and over and over again. The repetition of the rows of the lands in the soybean field or the curves in a rice field, those are visuals that if you spend your life in an area like the Mississippi Delta, they've burned into your memory. your brain. The way the land from above is partitioned off, so it almost looks like a quilt.

If you look at an aerial view, particularly of a space like the Mississippi Delta, and a very geometric quilt, every now and then with little lines running through it from rivers or creeks that kind of cut through the land, but otherwise it's pretty squared off. As I began to consider both my instinctual ways of making and where it might have come from, that's where pattern kind of, I think, makes its way into my life.

SP: Do you have any last things you'd like to say or anything you want to plug?

WJ: Well, first I can't thank all of you enough for allowing me to be a part of your family here at the Mary C. for the summer. And would love to come back many, many times. Like this is, it's been a really productive and peaceful summer for me. And those two things are very important for me. It's been really nice to get to know a little bit more about Ocean Springs as well. You know, Ocean Springs is very well known across the state of Mississippi in particular, but even over in Alabama, I'm in my third year in Alabama now, and when I mentioned that I'm spending my summer there, people in Alabama know about Ocean Springs and they know specifically about its’ connection to art and creativity. And so that's been great. This body of work for, shameless self promotion, will be installed next week at the University of Alabama gallery in Tuscaloosa, and it will be on exhibition through all of August and September. There is a reception Friday, September 6th.